Hi friends,

There is not just one “mental health crisis”.

I believe there are three distinct problems. And each requires a different set of solutions.

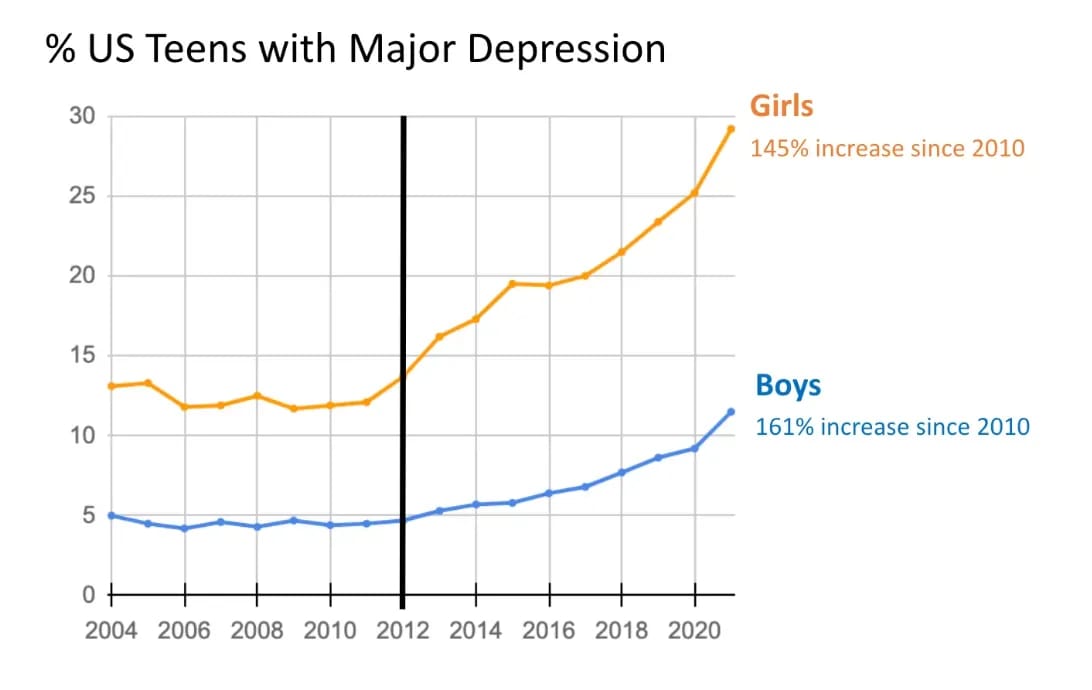

First, there is the youth mental health crisis; rates of depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicide are at alarming levels among young people. This drastic change in prevalence, the severity of the outcomes, and the degree of environmental change young people are experiencing creates, what I believe, is a distinct problem.

The second crisis is that of severe mental illness (SMI). This is not a crisis of increasing prevalence - rates are mostly constant - but a crisis of care. We don’t have good enough treatments for these people, and many don’t receive treatment at all. Their outcomes are terrible, and they deserve better.

Finally, there is a crisis of mild depression and anxiety among adults. That’s the focus of today’s report.

Some people call this group “the worried-well”, the “small D depressed”, or just those who are languishing.

Whichever phrase you choose, it is clear that something troubling is happening for this group in our society. And I’m not convinced more therapy is the answer.

1. What exactly is the problem?

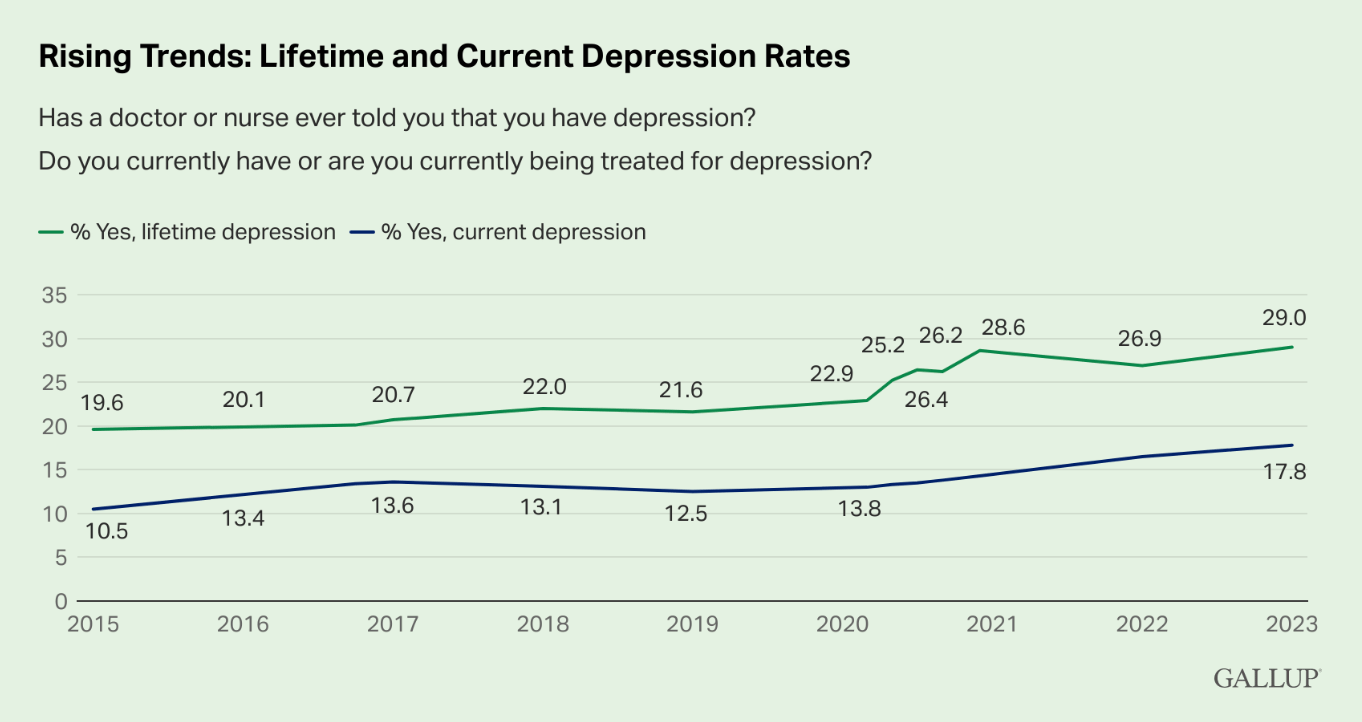

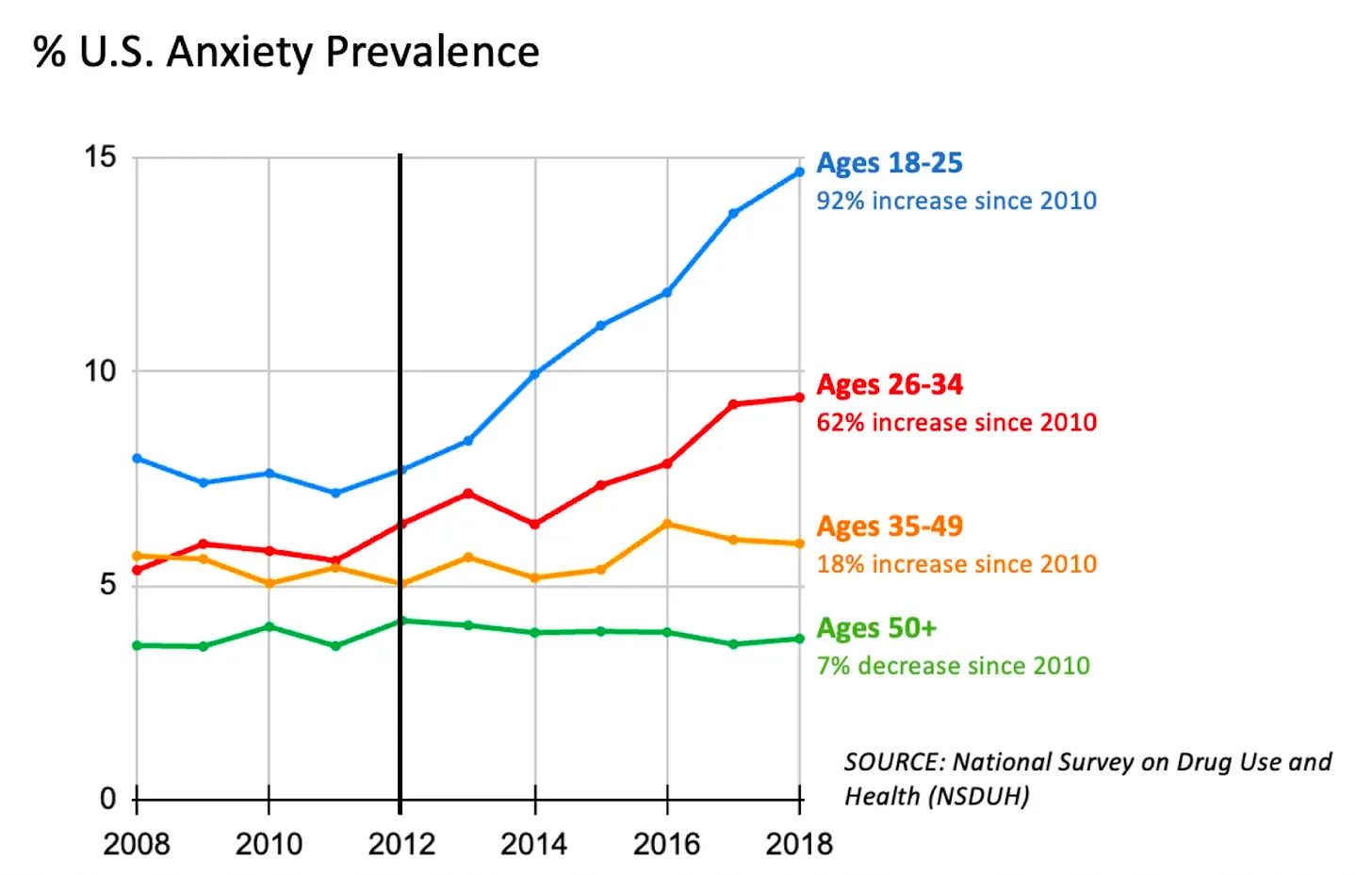

Firstly, we must more accurately define the problem. So let’s look at some data (woo, fun times). Rates of anxiety and depressive disorders have been increasing in US adults, and most Western nations follow similar trends.

When we double click on this data, we find that most of this increase is driven by younger adults - the prevalence of anxiety in those aged 18-26 has increased by 92% since 2010. For those over 50, however, prevalence has actually decreased by 7%.

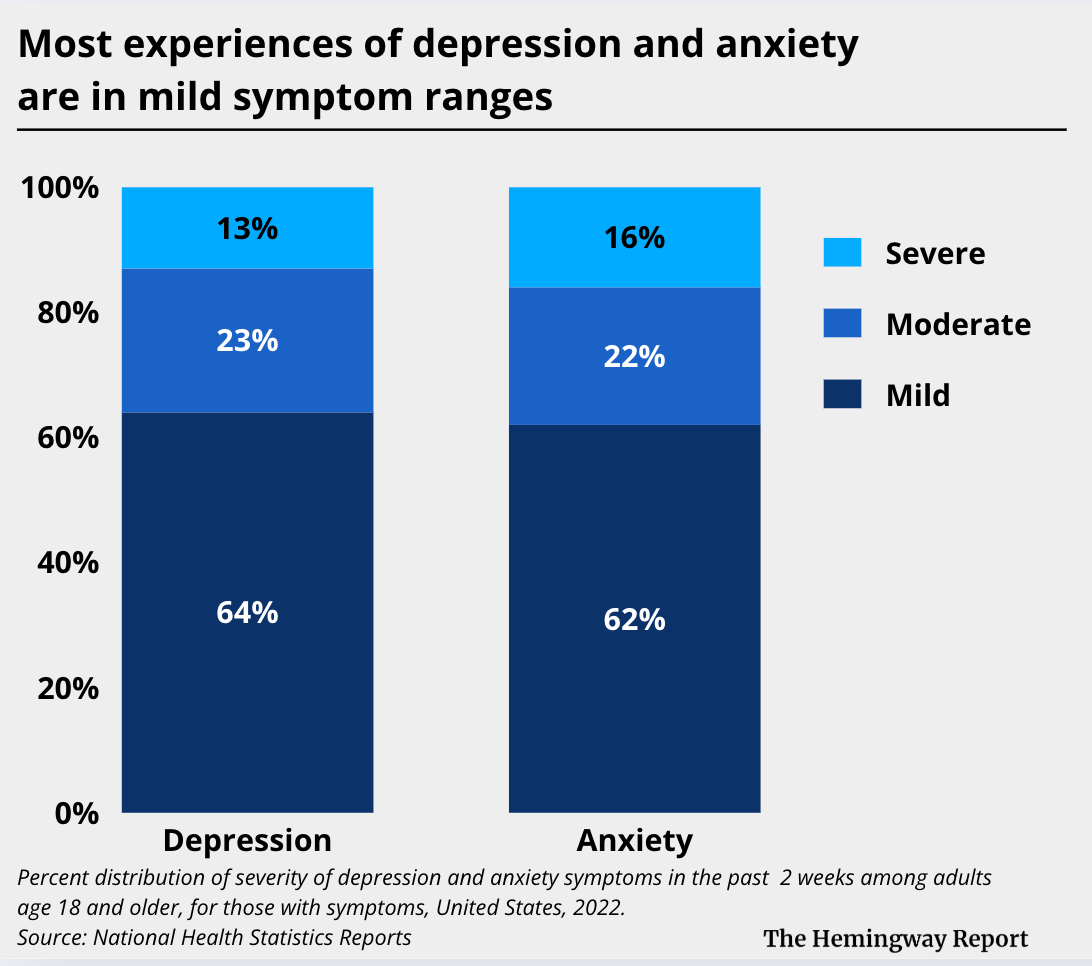

Double-clicking again, we find that the majority of these cases are for those with mild symptom levels. A 2022 report found that 65% of all symptomatic cases of depression were for mild symptom ranges. In anxiety, this number was 63%.

So, to more clearly define this problem, we have rising levels of mild depression and anxiety, primarily in young adults.

Even with these added criteria, that is still a population of tens of millions of people. And every one of those individuals is experiencing distress and wants help.

This is the population that many mental health companies are focused on supporting.

2. Why aren’t these people getting better?

I had been looking at this data for a while, and two questions kept coming up for me. Why is the prevalence of these conditions rising? And why aren’t those people getting better?

This was the focus of a recent discussion in the Hemingway Community. The unsatisfactory summary of our findings? We don’t really know.

We can point to credible hypotheses, but the research base is still lacking. Long-term outcomes, functioning measures, and causal analysis remain underexplored. In short, this is a highly complex issue, making such research very challenging.

Without conclusive evidence, we are left to our hypotheses. Let’s explore three of these hypotheses (they aren’t mutually exclusive).

Broader system and cultural changes have made mental health conditions more visible in the data. This may partly explain the rise in reported prevalence as expanding insurance coverage, improving diagnostic and reporting infrastructure, and reducing stigma have led more people to seek help, receive diagnoses, and be captured in formal datasets. The underlying change in actual distress and functioning is harder to determine. This is especially true for people with mild symptoms.

The social environment has grown more pathogenic. Political instability, technological disruption, economic uncertainty, and increased social isolation all create fertile ground for distress. A loss of authentic, co-regulating relationships and a decline in supportive communication skills may be compounding this distress. It’s hard to get good evidence on this, but if I had to bet, I would say this is a significant contributor.

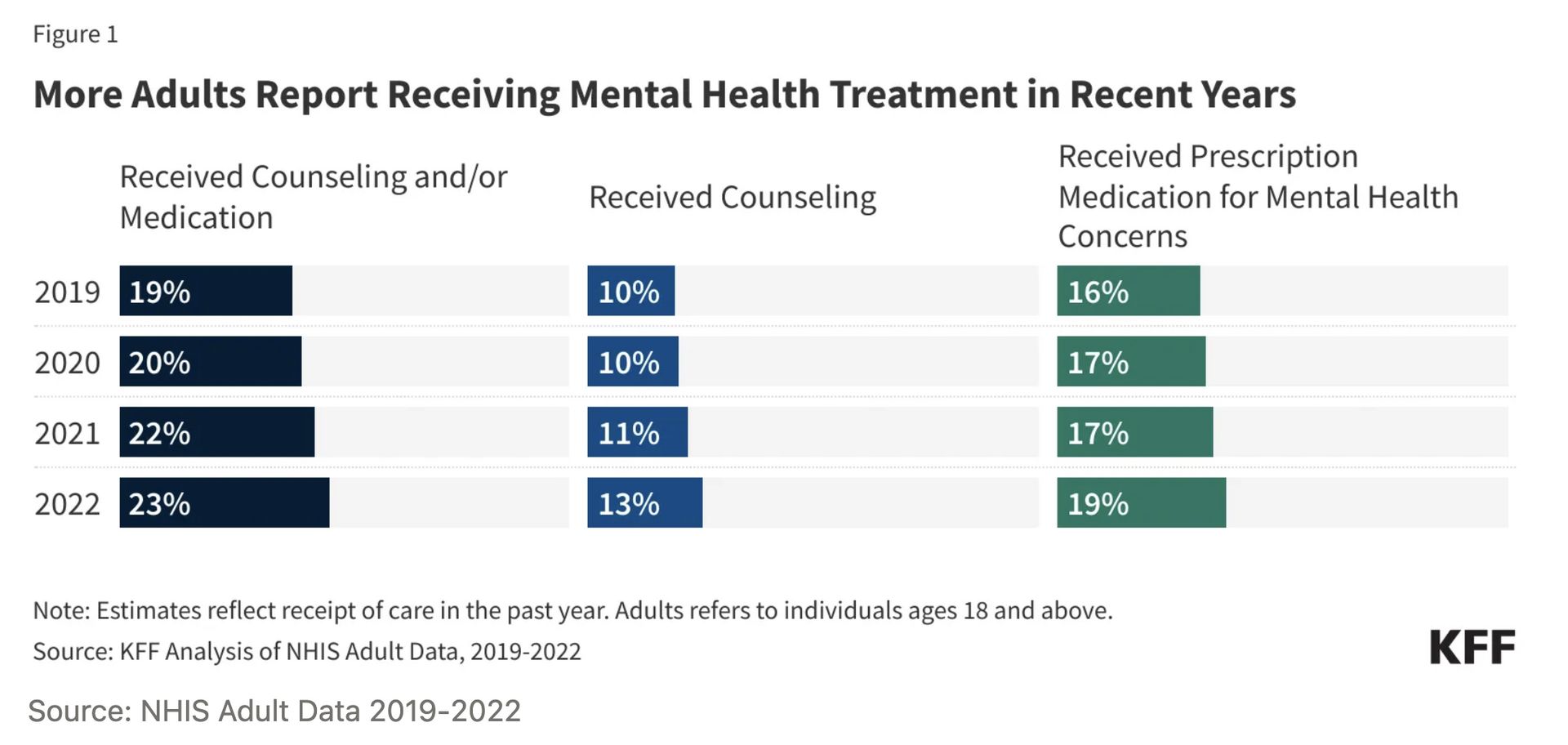

The quality and effectiveness of care haven’t kept pace with the rising prevalence. More people are getting mental health care today than ever before. The number of adults receiving counselling increased by approximately 33% from 2019 to 2022 - for those aged 18-26, this growth was approximately 45%. In 2022, it’s estimated that 23% of the US adult population received mental health treatment, either counselling or medication.

There are, of course, still people who need care and don’t get it. We should solve that problem. But to me, the more salient problem is that the efficacy rates of these treatments leave a lot to be desired. Yes, therapy can work. It worked for me when I was a kid struggling with OCD. It has worked for millions of people, thanks to the dedication and skill of therapists themselves. But there are millions more for whom therapy has not worked.

Many services remain short-term, transactional, or inconsistent, lacking the structure, therapeutic alliance, and outcome tracking needed for lasting impact. There has also been limited innovation to improve the efficacy of treatment. We still lack scalable, community-based models that treat the whole person and sustain wellness beyond clinical settings. Much of current care still fails to focus on improving day-to-day functioning or helping clients achieve concrete, behaviorally anchored goals that signal meaningful progress.

Thinking of this as a systems problem, we have more people coming into the system in distress, but our tools to treat that distress are limited, both in their efficacy and availability. This is surely one of the reasons why the prevalence of mild depression and anxiety persists in our society.

Join The Hemingway Community

If you want to participate in discussions like this, you should consider joining The Hemingway Community. We have almost 200 members and it’s a great mix of top founders, executives, clinicians, researchers and investors. Later today we are hosting an open discussion on regulation of AI in mental health. If you want to attend and join the community for future discussions like this, you can learn more and apply here.

3. Is more therapy the answer?

The ecosystem has facilitated the increase in therapy provision. I can’t stress enough - this is a largely good thing. But there’s a question I have heard from dozens of leaders across the ecosystem. One that they often don’t want to share publicly.

Is therapy really the best solution for these people?

When we think about how we can help reduce the suffering of the tens of millions of people with mild depression and anxiety, is the answer really more therapy?

We often talk about the supply-demand problem of mental healthcare. But even if we 10x’d the number of therapists, would this solve this crisis of mild depression and anxiety? I’m not sure it would.

Firstly, the efficacy rates of current treatments are not high enough to solve this problem. One meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapies for depression found that “more than half of patients receiving therapy do not respond and only one third remitted”. Combined therapy appears to deliver marginally better outcomes, but still, the majority of clients don’t respond. Across studies, these remission rates are largely the same.

But even if current treatments (e.g., therapy) had super high efficacy rates, it’s an unrealistic solution for this problem. The amount of therapy services required to treat this population group is overwhelmingly large. It’s unrealistic to think we can train that many therapists, and more importantly, that payers would pay for that amount of services (we struggle to get them to pay existing therapists what they deserve).

4. How do clinical diagnoses impact our ability to care?

I won’t wade into a discussion on DSM-V, but many argue about whether these conditions should be diagnosable medical conditions in the first place. Regardless of your thoughts on this topic, today, they are diagnosable. And that has implications for how they can be treated.

One thing a diagnosis does is open up reimbursement for treatment. This is helpful.

However, the existence of diagnostic categories also restricts what mental health organisations may be able to do to help these people with mild depression and anxiety.

Changes in cultural norms mean that we now label much of our everyday distress as anxiety or depression. When we go looking for help, that’s the language we use - “how to get rid of anxiety?” or “am I depressed?”. The problem is that these experiences sit on a spectrum: sometimes clinical, sometimes not; and even when clinical, they may be mild, moderate, or severe.

Regulation, however, doesn’t recognise that nuance. Unless a product is formally cleared by the FDA, it can’t advertise itself as a solution for anxiety or depression. Yes, that acts as an important safeguard for people in many situations. But it also leaves people with sub-clinical or mild symptoms caught in a gap.

They believe they need solutions for “depression or anxiety”, but the only solutions that can advertise that solution to them are approved clinical offerings. And so those are the services they are drawn to. When they then find out that the service is covered by their insurer, they are very likely to engage with it.

But perhaps it was not what they really needed. Perhaps something else, something more accessible and less costly, could have helped them instead.

5. Why is this coming to a head right now?

The question of how to help these people is getting brought up in so many of the conversations I’ve been having recently. This problem is coming to a head, and that’s for a few reasons.

Behavioural Health costs have risen sharply for insurers, and they are reacting by putting pressure on reimbursement rates. Employers are also tightening their budgets. Overall, payers are scrutinising their rising behavioural health costs and asking what outcomes those ever-increasing dollars are actually delivering. Much of this cost is for therapy services for those with mild conditions. Despite their best efforts, it’s hard for providers to show strong outcomes and good ROI for this group. Meanwhile, the underlying problem continues to grow.

6. What are we doing about it?

Mental health businesses are serving clients with these mild problems. And those clients, as well as the people paying them to provide that care, are wondering what they are doing to actually make those clients better. So what are they doing about it?

Some are trying to increase the capacity of therapists, using technology to allow them to care for more patients, but without increasing costs to the payer. Limbic are one example. This may allow for more supply (without significantly increasing costs), but it might not address the issues of treatment efficacy for this group.

Another group are trying to build scalable, sub-clinical interventions. This has been the approach of several digital mental health businesses over the years (most mental health apps could be categorised in this way), but the emergence of Generative AI has spawned new hope. Many businesses, like Slingshot, believe that they can support those people in the sub-clinical or mild symptom range through a conversational AI. This would certainly allow for scalability. The question is how effective it can be. It’s early, but I’m hopeful.

Others are combining sub-clinical interventions like this with a stratified or stepped care model. Headspace is an example. Their AI companion, Ebb, aims to deliver sub-clinical care and provide ongoing, personalised assessment so that if someone does need clinical care, they can be referred to those professionals within the Headspace ecosystem.

All of these approaches have merit. Some operate squarely within the healthcare system, and some on the edge. But I do wonder if the most impactful solutions may be completely outside of what we understand as healthcare.

The psychiatrist Allen Frances has strong opinions on this topic. He argues that we have medicalised normal distress and that many of these people with mild depression or anxiety do not need clinical diagnoses or even clinical interventions. Instead of increasing diagnoses and access to clinical interventions for those in mild distress, Frances believes we should be focusing on lifestyle interventions and supporting people to build greater resilience. I wonder what he would think of Spirit Tech. At a population level, he believes we should be investing much more in social determinants. His arguments have merit.

Frances also believes that at a population level, we would be better off if our clinicians could spend more time with those who have more severe illnesses. Finding better solutions (outside of therapy) for the cohort of people with mild symptoms would facilitate that. Again, it’s hard to argue against this.

6. Conclusion

Several businesses are focused on helping these people. Even though this population group may be classified as having “mild symptoms” as per our diagnostic criteria, they are still in distress, and they deserve support. For millions, therapy has been the support they needed.

But the question remains, is more therapy the best and most realistic approach for helping these people? And if it isn’t, what better solutions should we be building?

That’s all for this week. As always, I would love to hear your thoughts on this topic. I am very open to other opinions and being proven wrong. So please do share what you think.

Keep fighting the good fight!

Steve

Founder of The Hemingway Group

Appendix: An explanation of our three mental health crises

First, there is the youth mental health crisis; rates of depression, anxiety, self-harm and suicide are at alarming levels among young people.

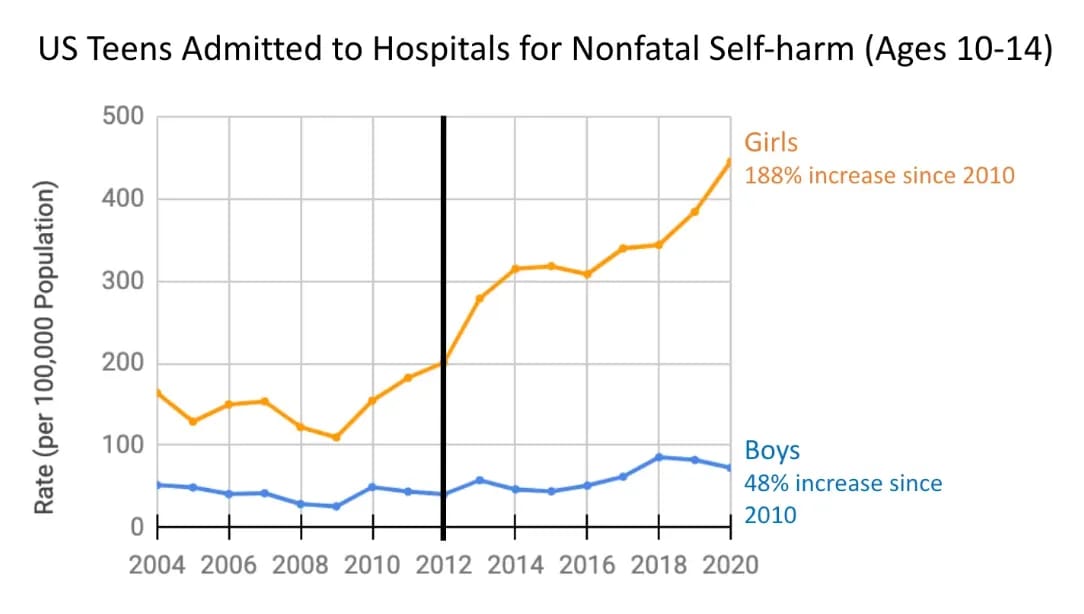

The number of US teenage girls with depression has increased by 145% since 2020. For boys, it has increased by 161%.

Hospital admissions for non-fatal self-harm have also increased significantly, especially in girls.

But there is one statistic that I just can’t get out of my head…

9.5% of US high school students have attempted suicide (CDC Data). What the hell? One in ten high school kids has actually attempted to end their own lives. For LGBQ+ groups, this increases to almost one in five.

The drastic change in prevalence and the severity of the outcomes suggests to me that this is a distinct and worrying crisis.

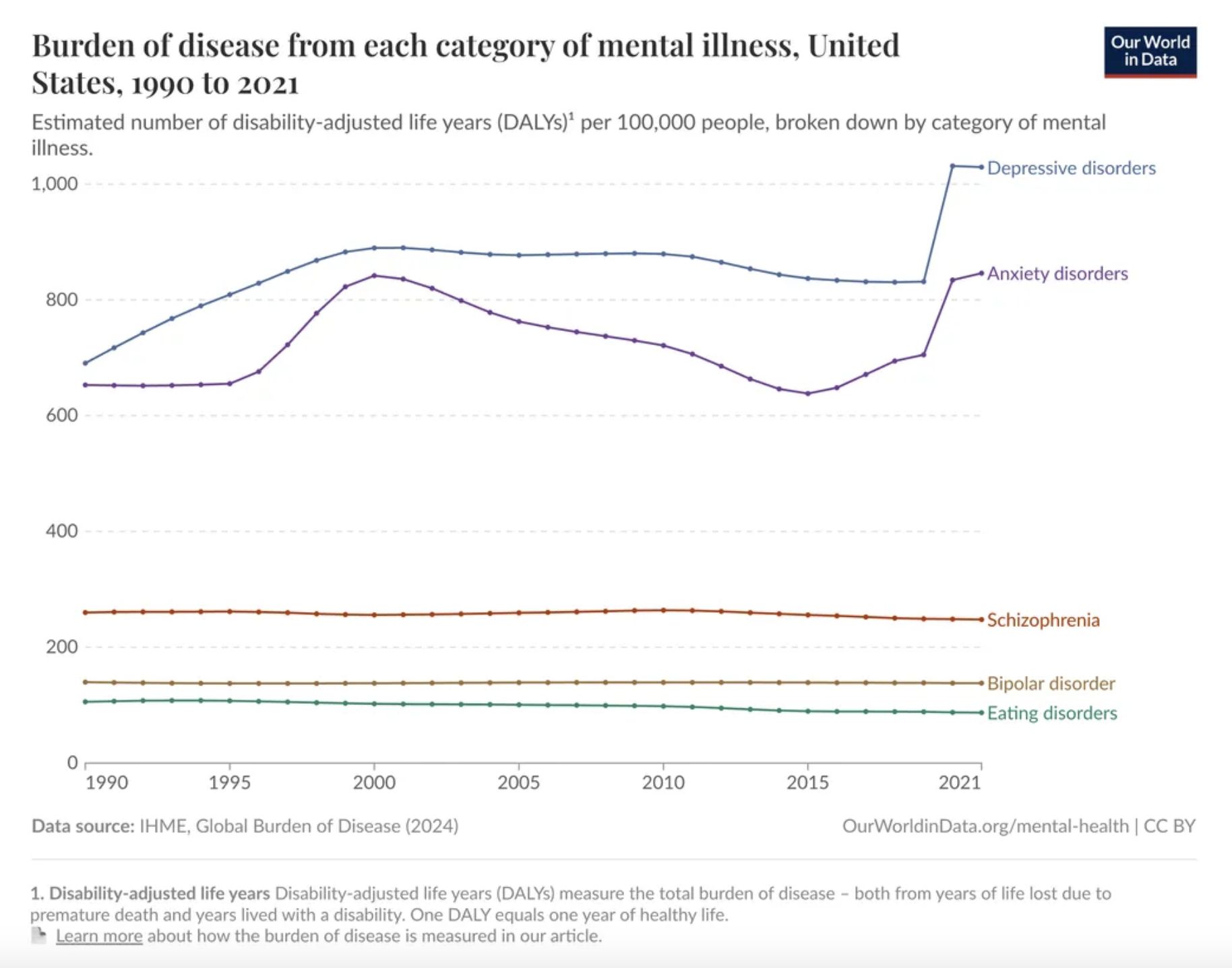

The second crisis is in Severe Mental Illness.

Here, prevalence has remained pretty much constant over time - roughly 5%. It is not a crisis of prevalence, but a crisis of care.

Outcomes for people with SMI are still poor - patients with severe mental disorders (schizophrenia, major depression, bipolar) have a reduced life expectancy of 10–25 years compared with the general population (source). Many go without treatment. And for those who do get treatment, the options are often limited, expensive and with significant headroom to improve their efficacy.KFF

The third area of crisis is in adults with mild depression and anxiety.

This is a crisis of prevalence - rates of anxiety and depressive disorders have increased significantly. It is also a crisis of care, but a different kind of care crisis, which I discuss in the full report above.

Most of this increase is driven by younger adults - the prevalence of anxiety in those aged 18-26 has increased by 92% since 2010. For those over 50, prevalence has actually decreased by 7%.

Figure 3. Percent US Anxiety Prevalence. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). Image source: After Babel

The lines between these crises are, of course, a bit blurry. But despite it not being a perfect segmentation, I still think it is a helpful way for us to dissect this broader problem.