Hi friends,

Crisis care for mental health patients is broken. In fact, it’s beyond broken. It’s desperately failing millions of people - especially in the US.

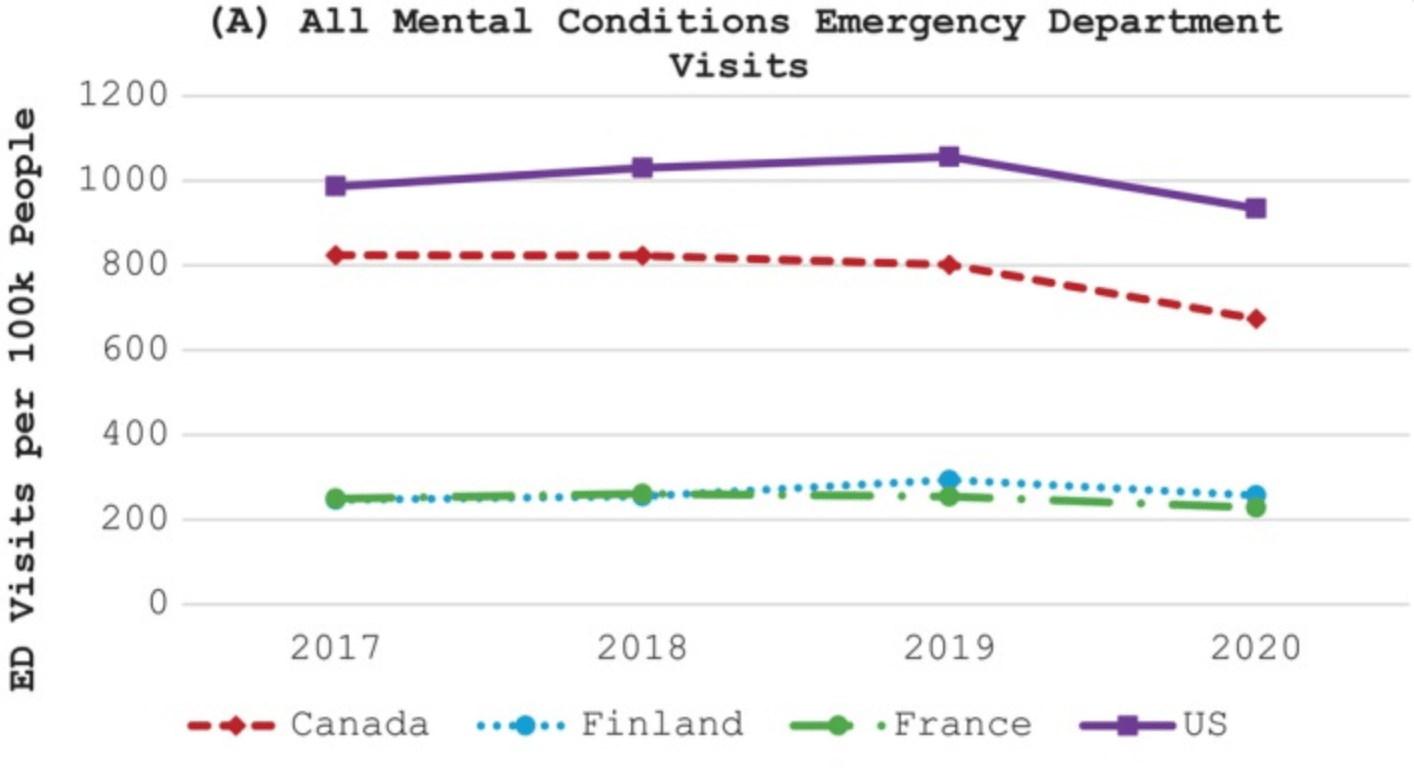

One in every one hundred Americans will visit an ED for a mental health-related concern each year. That’s four times higher than countries like France or Finland.

Comparison of Mental Health-related ED visits across countries. Source: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11622279/

In actual terms, this translates to over ten million mental health-related ED visits from adults every year. On a personal level, I would bet you know someone who has been to an ED as a result of a mental health challenge.

But EDs were not designed to care for these people. Whilst the staff do their best, they do not have the time, resources or training to adequately deal with these kinds of presentations. For those patients who may need to be admitted, psychiatric inpatient beds are regularly not available, and so they are turned away or boarded in the EDs.

Many of these patients don’t need to be admitted to inpatient care. In fact, many of them don’t need to be in the ED at all. Most are non-violent, non-dangerous and don’t want to be there. The experience of visiting the ED rarely helps them, and in many cases, the trauma of the experience can often make matters worse.

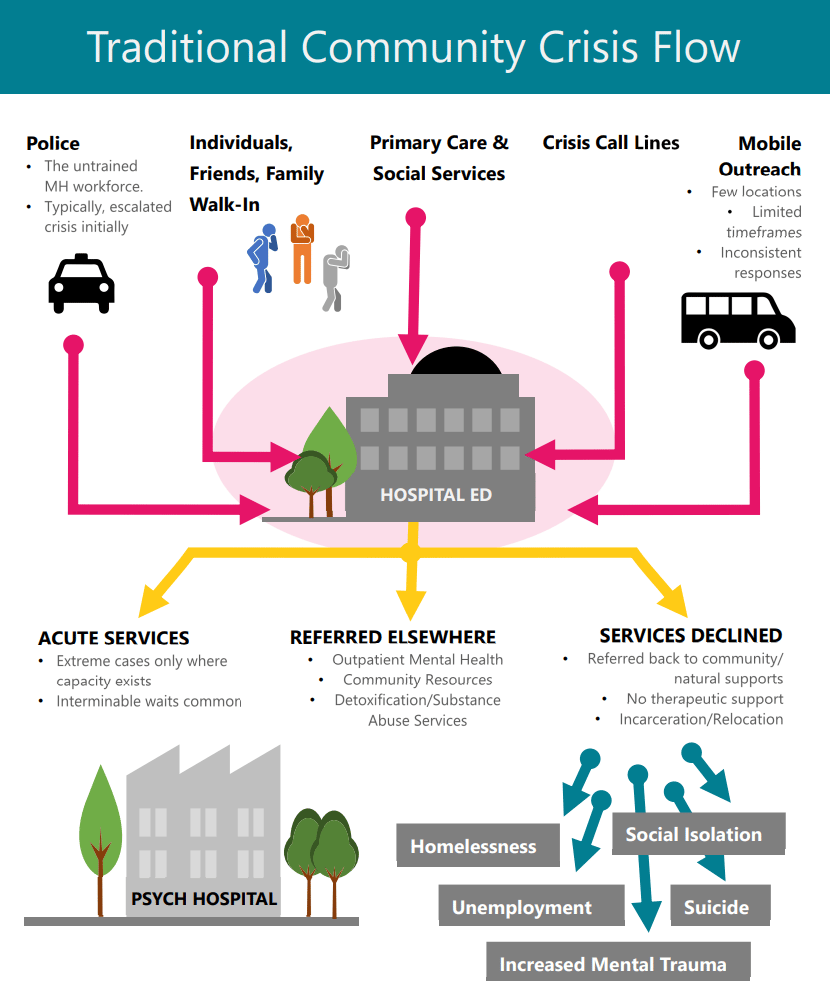

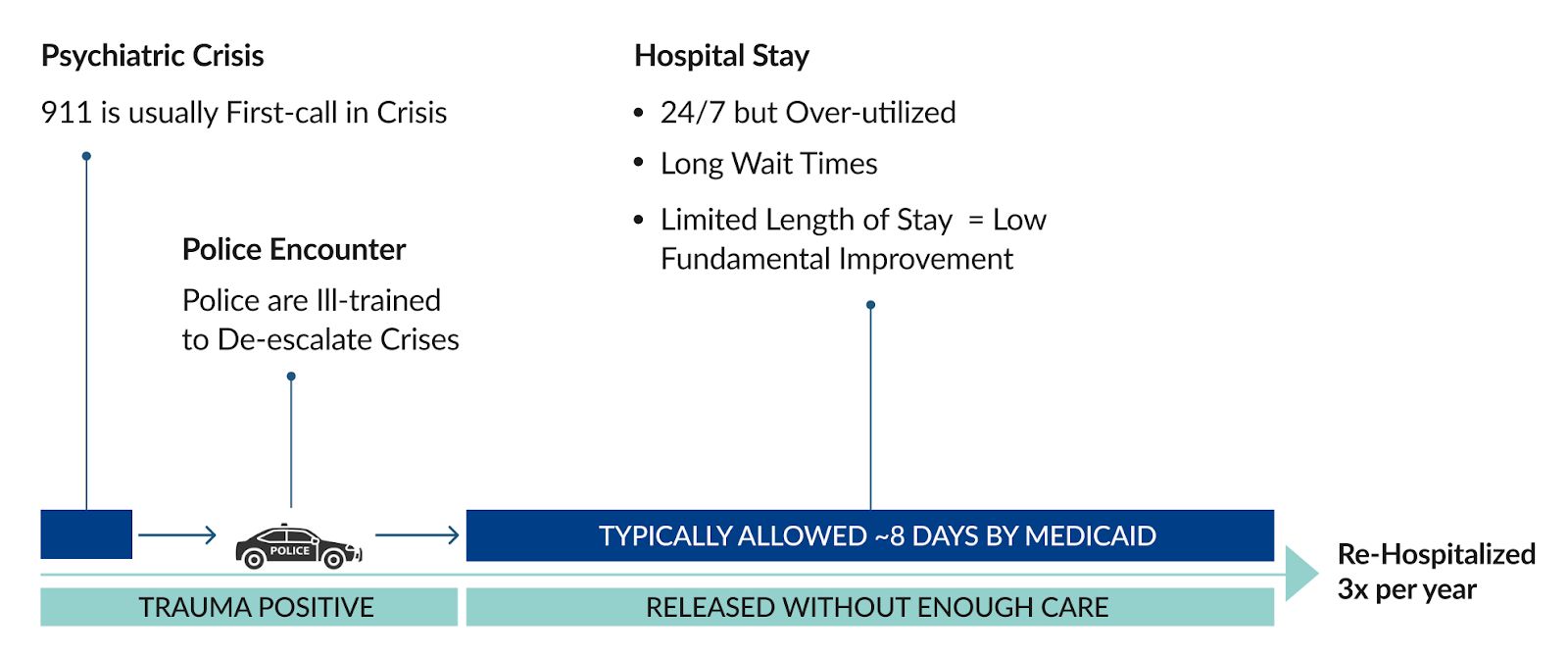

If we look at this experience for an individual, we can see why it can be so traumatic.

These stories usually begin in a moment of crisis. Perhaps someone is suicidal, has an acute anxiety episode or a psychotic break. A family member or someone from the community gets concerned. These people don’t really know who to call, so they often dial 911.

The police arrive and bring the patient into care. While police are trained to be effective in many situations, minimising trauma and supporting patients through a psychiatric crisis is not top of that list - to be fair, it just can’t be. So they pick the person up, put them in the back of their car and usually bring them to an emergency department - or a CPEP (Comprehensive Psychiatric Emergency Program), a hospital-based emergency service specifically for psychiatric patients.

The typical journey for someone in a mental health crisis. Source: https://crisisnow.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/CrisisNow-BusinessCase.pdf

The patient arrives, goes through big metal doors, is placed in a room by themselves - often they’re asked to take off their clothes to be searched, given a smock and brought through. Then, they wait… Often for several hours.

Some data from 2016 showed that 23% of psychiatric patients wait in the ED over 6 hours (versus 10% of medical patients), and 7% wait over 12 hours (source). When they get seen, they are either admitted for an inpatient stay or discharged back into whatever environment they just came from - this environment is often the reason they are in crisis in the first place.

Remember, this is someone who is already going through a psychiatric crisis, and now they are being brought through this clearly traumatic experience. Again, the police or hospital staff are in no way to blame here. The whole system is just not designed for these patients, in these situations.

One ED clinician sums this up well:

These people go to the ED, not because they need or want to be there, but because they have nowhere else to go.

This is what Town Home is changing. And for at least one million of these people, they believe they have a much better alternative.

While the issue is most pressing for patients, other parts of the health system feel the problem too. ED visits and hospitalisations are expensive for payors.

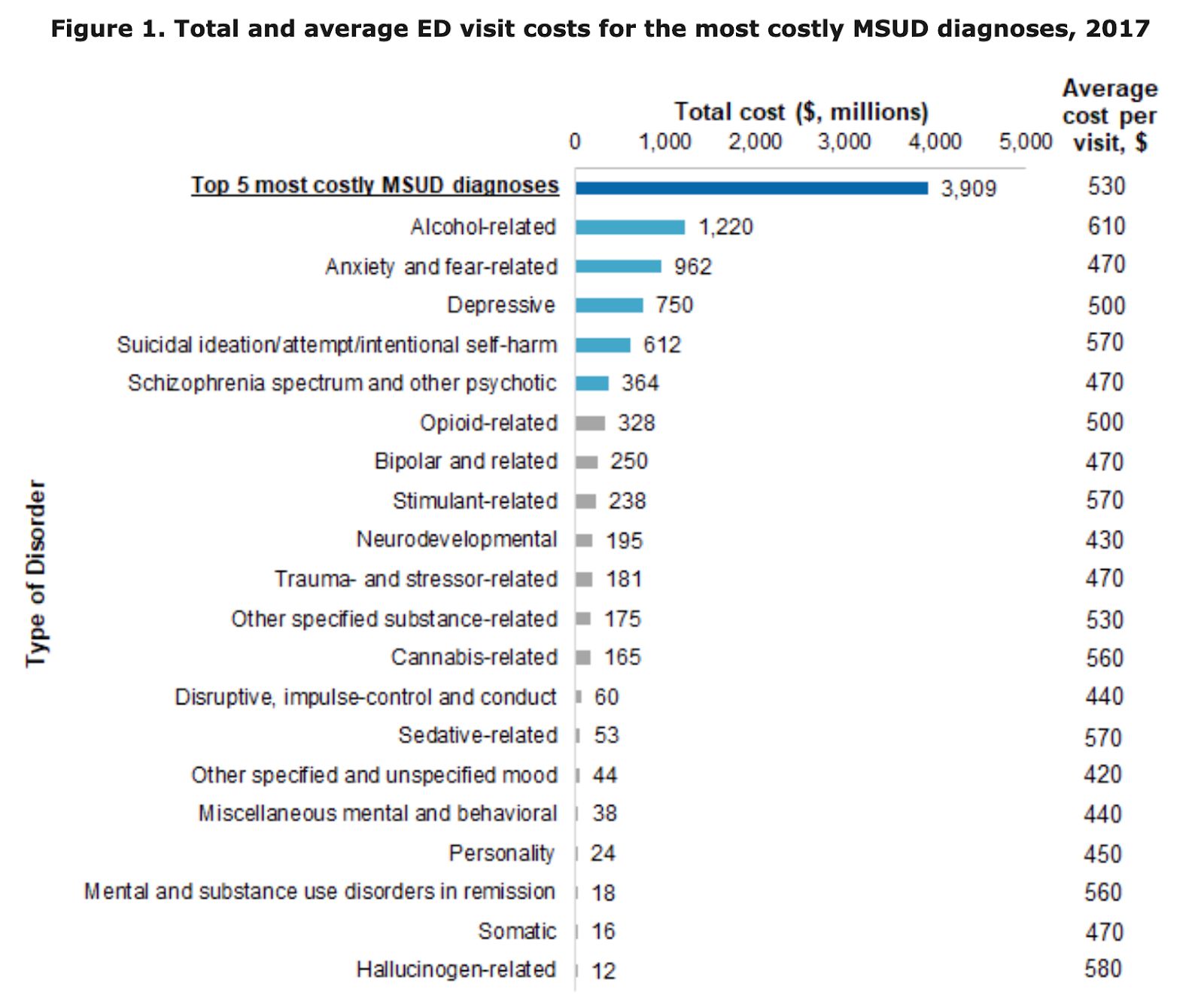

The average cost to a payor for a single mental health-related ED visit is over $500, with alcohol use disorders as well as anxiety and depressive disorders being the three most costly indications.

Costs of ED visits for Mental Health and Substance Use Disorders. Source: Source: https://hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb257-ED-Costs-Mental-Substance-Use-Disorders-2017.jsp#:~:text=,billion%20total%20ED%20visit%20costs

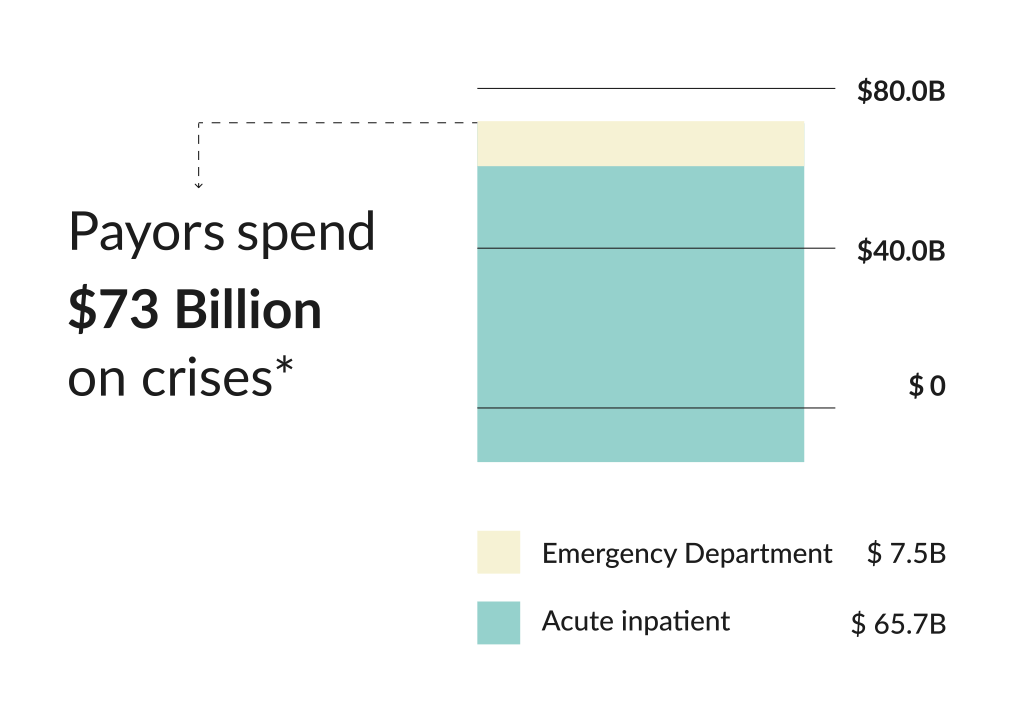

When we combine this with the massive volume of visits and hospitalisations each year, we see that payors spend $73B on crisis care for mental health-related issues each year. $66B of that is for acute inpatient services and $7.5B for ED visits.

The total annual cost to payors of mental health ED visits and acute inpatient stays. Source: https://crisisnow.com/

Hospitals struggle with the challenge, too. Approximately 12% of all adult ED visits are now mental health-related. These departments and their staff are ill-equipped to adequately deal with these patients.

It should be unsurprising that outcomes for this group of people are poor. Rates of ED revisits and hospital readmission are high. One study from 2016 suggested that 25% of those presenting at an ED with a mental health condition (who were non-homeless) would revisit the ED within 30 days, and 2.6% would be readmitted to hospital. This is a disaster for patients, hospitals and payors.

Source: TownHome Health

The system is clearly failing.

But while this problem has persisted, there have been pockets of passionate people building a better solution.

Introducing Dr. Donna Friedman

In the 90s, Donna Friedman was working as a marketing manager for Nestea Iced Tea. She had an older brother who had developed a psychotic disorder around that time and had become very ill. He was the oldest sibling, engaged to be married, and his psychotic break had a huge impact on their whole family.

Donna got obsessed with understanding what was happening for her brother and decided to go back to graduate school to study psychology. Donna dove deep into understanding her brother’s experience and how those kinds of conditions develop. Today, she holds two masters degrees, a PhD, as well as completing a postdoc. When she was in graduate school in New York, she got an internship at Mosaic Mental Health, a non-profit organisation in the Bronx. They soon offered her a full-time position, which she took, starting out as a clinician working in community mental health programs. After a few years, Donna moved into supervision, then into program directorship, into a deputy executive director role and ultimately, in 2017, Donna became executive director of Mosaic.

Mosaic has run community mental health programs around New York for years, and Donna had been at the heart of that, both on the front lines as a clinician and then as the organisation's leader.

As she took on her role as executive director, she became interested in ways to better care for people in moments of crisis. She had come across a new Swedish model which focused on demedicalising the approach to caring for people with serious mental illness in acute conditions. The core aspects of the model were enabling people with lived experience to deliver care and ultimately, to remove trauma from the experience of psychiatric crisis care. Mosaic was already running the largest crisis respite centre in the city, and Donna was thinking deeply about what they could do to improve the experience of people in psychiatric crisis.

During COVID, she got a chance to test this new model.

Respite centres had been closed across the city, but demand for acute mental health services had remained. Donna was eager to provide a solution for hospitals overwhelmed by demand for psychiatric crisis care.

Can I just take a moment to say that I think Donna is a legend? After spending an hour with her, I felt compelled to hijack the conversation and ask Donna for life advice. Unsurprisingly, she was great at that too…

But back to the story of TownHome…

The commissioner accepted Donna’s offer, and psychiatric patients were taken out of state hospitals and transferred to Mosaic’s respite centre operating under this new peer model. After they had run this model for a while, Donna found that the staff members with lived experience were capable of working with much higher acuity patients than she had ever anticipated. The model appeared to work, and coming out of COVID, Donna felt they now had a massive opportunity to transform psychiatric crisis care.

By this time, Donna had spent decades working in community mental health in New York. She made a massive difference in the city, but was thinking about what more she could do. She also knew that it would be difficult to scale the non-profit model further afield. If you can make it in New York, you can make it anywhere… right??

Then she got a call from Charles.

Charles Raisch had had a successful corporate career, but at the time, he was looking for a meaningful new project in mental health. He saw huge potential in the model that Donna had built and tested over fifteen years with Mosaic. He believed that forming a business around the model Donna had created would facilitate the scale that Donna was looking to achieve.

And so, in 2023, TownHome was born.

A Hospital Alternative for Mental Health Crises

At its core, TownHome is an alternative to hospitals for people experiencing a mental health crisis.

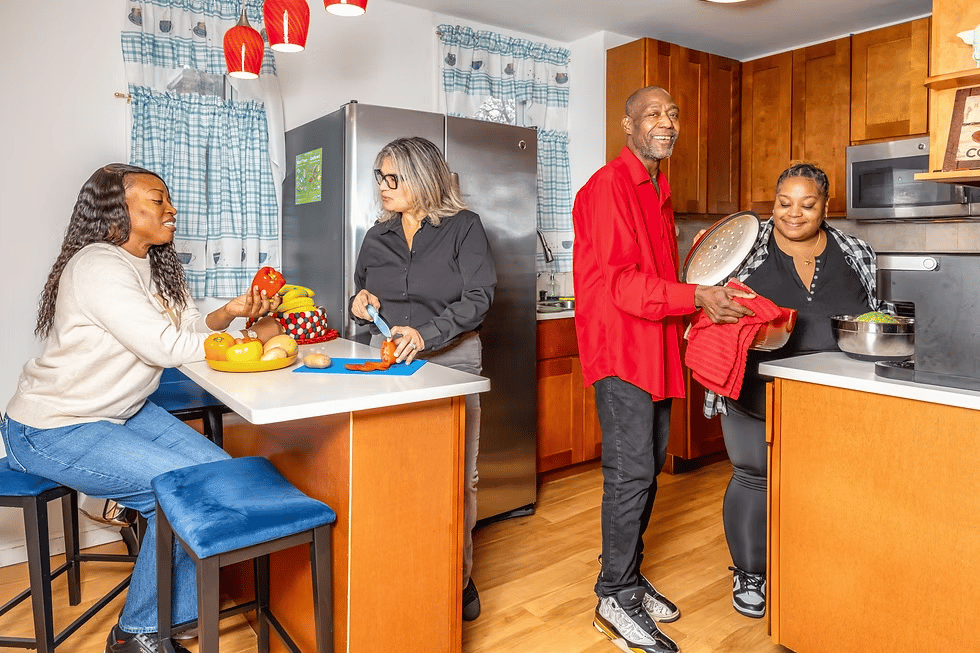

Instead of going to the ED or getting admitted to the hospital, people can go to a TownHome where they can stay for up to twenty-eight days, all while getting cared for by a peer workforce. The homes themselves are single-family houses - 12 private bedrooms, a shared kitchen, common spaces for meals, music, meditation, video games, and group activities. Guests are free to come and go, have visitors, and participate in a gentle, structured routine - engaging in everything from cooking classes to peer-led group therapy, to one-on-one support sessions, to practising yoga or meditation.

The living area of a TownHome house. Source: TownHome

Earlier, I brought you through the journey of someone in crisis getting picked up by the cops and brought to an ED. Let’s contrast that with someone in the same situation, but with access to TownHome.

When that person first goes into crisis, their family can ring Town Home directly. The folks at Town Home pick up, ask a few questions and then invite the person to come by the home to stay. If transport is an issue, TownHome will send an Uber. Of course, they also get lots of referrals from hospitals and police, but the opportunity to go directly to TownHome removes much of the potential trauma from the experience. When the guests arrive, they are greeted by one of TownHome’s peer workers - almost always someone from the community who has lived experience and an ability to relate to the person walking through the door and their situation.

No metal doors, no change of clothes, no loud ED, no doctors in white coats.

“The plan is to have them on the couch with a cup of tea within twenty minutes of arriving. Immediately, you'll see people’s shoulders drop a little as they realise, oh, this isn't a scary hospital”Charles Raisch

“Kind, calm, make-yourself-strong kind of care”

TownHome offers 24/7 care to its guests, combining emotional support, skill development, and access to clinical care. So far, their model has been very successful, and I think it’s down to a few things.

First, they utilise a peer workforce. These workers are able to offer culturally relevant, tailored support to TownHome guests. This can include one-on-one peer counselling, group therapy, and daily emotional check-ins.

Each house also has a licensed, experienced social worker as the director of the home. These people oversee the house and manage responsibilities like coordinating with external clinical teams. They can liaise with each guest’s healthcare team to facilitate therapy, manage medication or support whatever other clinical needs their guests have.

TownHome places a significant emphasis on enhancing daily living and recovery skills; cooking meals, managing hygiene routines, grocery shopping, and creative activities like spoken word nights or music sessions.

Related to this, one of the elements of TownHome’s model I like the most is their focus on enhancing social determinants of health. Staff spend a bunch of time helping guests navigate benefits, insurance, medication refills, dental visits, ID cards, job applications, digital literacy and housing. Hospitals do a bad job of treating these social determinants, and people are often dumped back on the street or into social situations that are destined to lead them to rehospitalisation and declining health outcomes.

Finally, they don’t end their support when someone leaves the house. They send follow-up texts to guests after discharge, keeping the door open and the relationship warm. They maintain an ethos of ongoing community, inviting guests back for events. About 7% of previous guests end up being hired as peer workers. They’ve also recently launched a new hybrid alumni program that combines virtual care (using real peers overseeing AI support) with in-person meetups (around holidays, for example). These efforts create a feedback loop of healing, purpose, and employment, one of the major contributors to the outcomes they are able to generate.

Above all, it just feels human. It feels genuine, personable and full of compassion. The kind of place where healing can take place. The kind of place you’d want a loved one to be if they were going through a mental health crisis.

A TownHome House. Source: TownHome

A Business Model with >50% Margins

It’s clear that this home-based model of care is capable of great things. So why are they not ubiquitous across the country?

What’s held this model back in the US has not been outcomes. It’s been economics. The crisis homes that do exist in the U.S. have been predominantly run by non-profits and are deficit-funded. For the past few decades, Medicaid rates have just been too low to make money on this service, bed counts were often too small, and there was no incentive to grow or invest in additional services or products to support the sustainability of the model. Of course, these organisations still offer life-changing care to thousands of people, but that is a single-digit percentage of the people who could benefit from a crisis home.

That is beginning to change.

THR Pro: A Membership for Mental Health Operators 📣

As a THR Pro member, you’ll be joining a group of hundreds of the world’s top mental health founders, clinicians, researchers, executives and investors,

You’ll also get access to additional insights and data each month, including the full insights from our most recent research report on How People are Using AI for their Mental Health and our article on What Happened to the Mental Health Startups of 2020.

NB: Applications are now open for the next cohort of our vetted Slack community. Become a THR Pro member to apply.

In 2022, New York doubled its Medicaid reimbursement rates for licensed respite homes. That change gave the model enough oxygen for teams like TownHome to build a facility that could operate with strong unit economics and a chance to reinvest in infrastructure.

The financial model for each TownHome house is quite simple.

Each home has 12 rooms, reimbursed at approximately $650 per night. The homes cost around $10,000 per month to lease, and most of the other costs are staffing. At full occupancy, TownHome’s facilities operate at roughly 50% margins. At 70–75% occupancy (which is rare given the high demand for their services), the margin still holds steady around 40%. That level of efficiency is extremely rare in behavioural health delivery. Overhead costs are low and Charles reckons they can, and should, remain low as they expand.

The model also improves dramatically under value-based care contracts. Most of us are aware that the majority of healthcare costs for a population with mental health diagnoses come from emergency visits and hospitalisations. Most behavioural health companies tell a story of how they reduce these costs, but for most outpatient care providers, it’s often difficult to directly show that impact. Because TownHome directly deals with a population with such high rates of ED revisits and rehospitalisation, and because they are dealing with them in an intensive, residential setting, and frankly, because they do such a good job, they have the potential to make these cost savings a reality for payors.

A peer-reviewed study of similar programs in NYC found that guests reduced their hospitalisations by 75% compared to their prior year baseline. The average savings to Medicaid per person was over $25,000. TownHome is currently piloting some incentive-based payments with payors, but with potential savings this large, there’s a huge opportunity for them to more aggressively pursue risk-based contracts. If successful, that could push their nightly rates closer to $900–1,000 per night, moving margins even higher.

Of course, we will have to see if these results can hold for TownHome and be consistently demonstrated in new locations as they expand.

Capital Efficiency To Enable Scale

Donna and Charles see the potential for a distributed, scalable, and financially self-sustaining network of small facilities, each deeply embedded in the community they serve. They’ve demonstrated that each home can be profitable and operate sustainably. They also believe they have a model that will allow them to open several more homes around the country, whilst remaining highly capital efficient.

Their first facility opened in Brooklyn in September 2024. Within eight weeks, it was full. In January, they applied to open a second facility in Harlem. In March, a third in Queens. In parallel, they’ve partnered with the Mayo Clinic to launch a site in Minnesota and are in active discussions with the City of San Francisco. A proposal has also been submitted to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to establish a TownHome-style program in every state. That would be huge.

The model to facilitate this expansion depends on a pod-like structure. Each home is a self-contained operation: a local team, its own budget, and community-responsive programming. The central organisation handles regulatory approvals, contracting, and light administrative support. The rest is decentralised.

That approach unlocks a few important advantages. First, the homes can reflect the language, culture, and needs of their guests. In Brooklyn, that means peer staff who speak Creole and Spanish. The food and the activities in each home are also adapted to the local community. Future homes might specifically serve LGBTQ+ communities or groups of new mothers. The beauty of this model is that it has the ability to develop tailored services for each community, whilst maintaining core standards around care quality and operating efficiency.

Second, the model scales without introducing central overhead. There is limited need for a national sales team or large clinical operations organisation. The lead social worker and peers build local relationships with providers, law enforcement and everyone else who is involved in crisis support. Referrals come from community clinics, law enforcement departments and hospitals. The business doesn’t need to spend a bunch of money recruiting clinicians or acquiring clients - it’s pulled forward by the system’s unmet need.

There are hardly any capital costs. Yes, they are building some technology to support their service. They have their own crisis respite EHR, patient portal and virtual alumni program. But this is ancillary to their model and, relatively speaking, has been inexpensive to build - they’ve done it all for under $150k so far. They don’t need to buy real estate, train AI models or hire large teams. It’s really bloody efficient, which is one of the reasons they have only raised $2.7M to date.

That capital has supported the development of five sites - either currently in operation or in advanced planning. The primary constraint now is not funding. It’s regulation. Approval timelines are long, and capacity remains artificially capped, which is frustrating.

There is a potential downside to such an efficient model, however.

As we play this forward, given the new Medicaid rates, the success of the model and the ROI it can generate for payors, we can expect more players to enter this space. Overall, that would be a good thing. Charles and I agree on this. But there is a question about how defensible TownHome’s strategy is as it grows.

There’s a risk they won’t get many returns to scale. If a similar centre pops up in a specific community, could they do just as good a job as a TownHome house, with the same unit economics? Perhaps, but the amount of operational experience, knowledge and reputation that Donna and the team have acquired is a genuine asset. There are very few people, if any, who know more about running a crisis centre like this. Also, there will likely be some benefits to being bigger; it will be easier to negotiate payor contracts, and there will be some marginal benefits from best practice sharing across locations.

Serving the Needs of One Million People

There is essentially no market risk here. The U.S. has over 6,000 hospitals. Charles believes at least 1,000 of them could benefit from having one or more crisis homes nearby (there are currently only 30 of these in the whole country).

That implies a potential footprint of 12,000-16,000 beds nationally. At the standard reimbursement rate of $650 per night, that’s a $2.8 - 4 billion opportunity. And frankly, this is conservative.

The cool thing about this model is that it can continuously adapt to the local needs of communities and specific population groups. Charles is excited about what they could do in future to expand and serve groups like new mothers or LGBTQ communities.

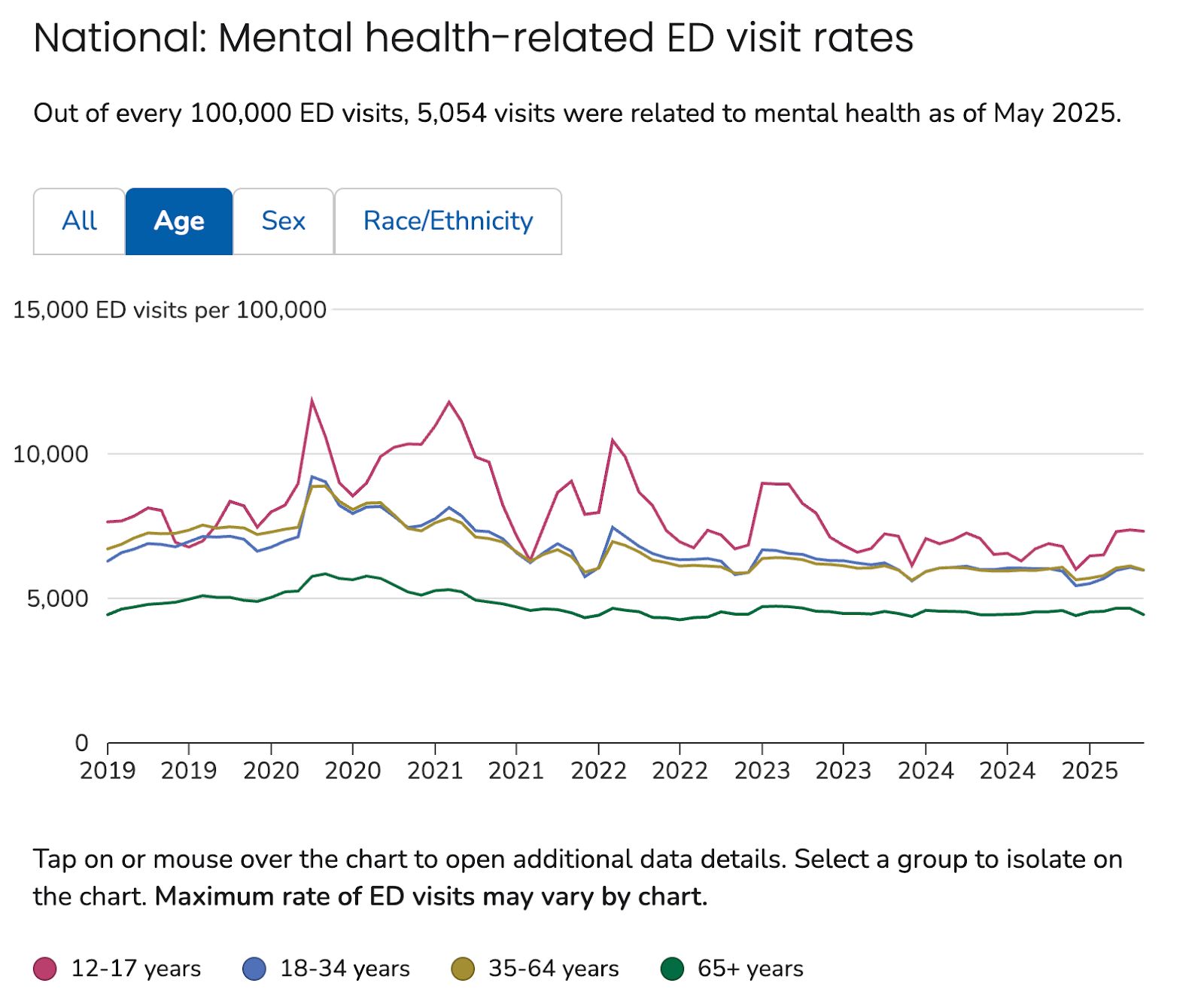

Youth populations are another large market to be served. Unfortunately, rates of ED visits for mental health-related issues, as a proportion of all ED visits, are highest amongst young people.

Rates of ED visits are highest amongst young people. Source:

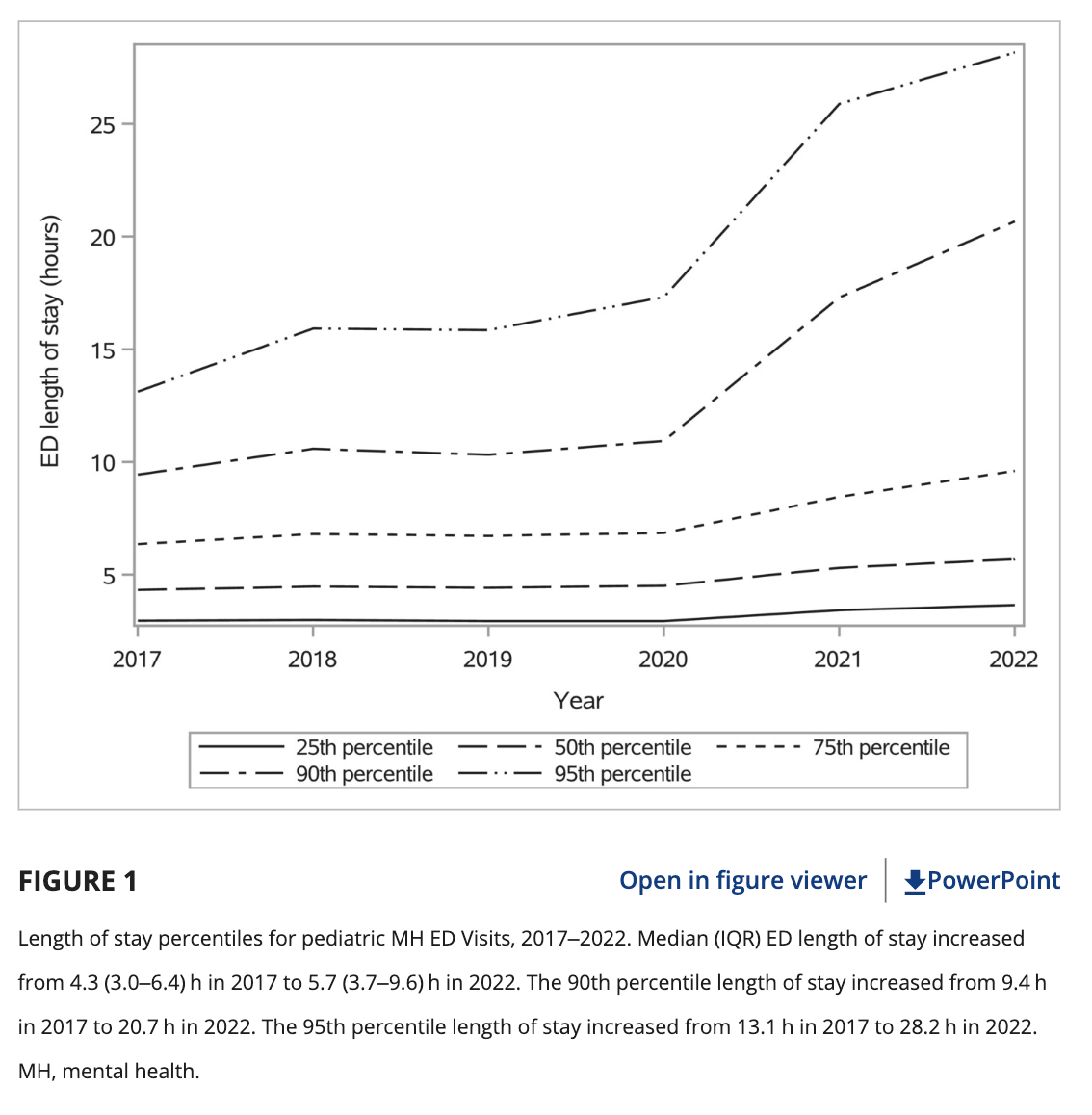

And the experience for these children is only getting worse. ED length of stay has been increasing rapidly post COVID.

Length of stay for pediatric MH ED visits. Source: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/acem.14910

While TownHome currently only serves adults, there is so much potential for them to expand their model to serve other demographics and to do so in the culturally relevant, community-based and personalised way that has facilitated their success so far.

I think this is a wonderful business.

It’s innovative, not in a technological way, but in the care model, infrastructure and business model they have created. It solves a nasty problem that is experienced acutely by patients, providers and payors. It’s capital efficient, scalable and has a clear growth roadmap. It will also benefit from low (potentially negative) client acquisition costs. And from the data so far, it works really, really well, both in terms of patient outcomes and ROI for payors.

Above all, this company has soul.

Look, I am Mr. “Data-Driven”, ensuring that we always remain grounded in evidence and analysis. But sometimes you need to realise when something just feels right. This feels right. It’s human, it’s compassionate, and I want to see it succeed. I hope you do too.

If you enjoyed this story, please participate in our State of the Industry Report

We want to know what your experience has been of the mental health industry in 2025 so far. Could you please take a few minutes to share that with us in our survey?

It’s short, anonymous and asks you some straightforward questions about your experience of the industry so far in 2025. Many thanks to everyone who has already contributed their insights. The findings will be shared in an edition of The Hemingway Report soon.

That’s all for this week. If you like what TownHome are doing, feel free to learn more about the business, Donna and Charles.

And as always, reply to this email and let me know what you thought. If you are building something genuinely impactful (like TownHome is), please get in touch. I’m always interested in hearing stories of interesting organisations.

Keep fighting the good fight!

Steve

Founder of The Hemingway Group

P.S. Feel free to connect with me on LinkedIn

P.P.S. If you want to become a THR Pro member, you can learn more here.